BOOKS:A LOOK INTO THE PAST

From the oldest books to where they are today:

The video above will show you the history of books.

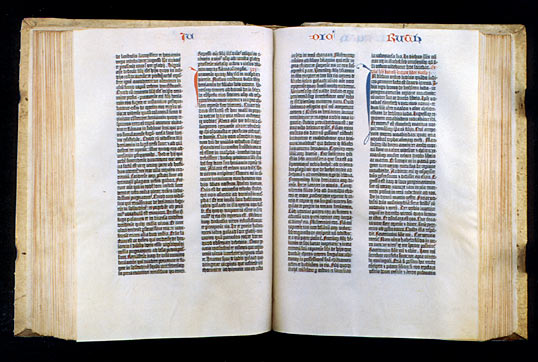

Copy of The Gutenberg Bible

Before we can talk about the past of the book industry,

we need to touch on the basics of a book:

Paper

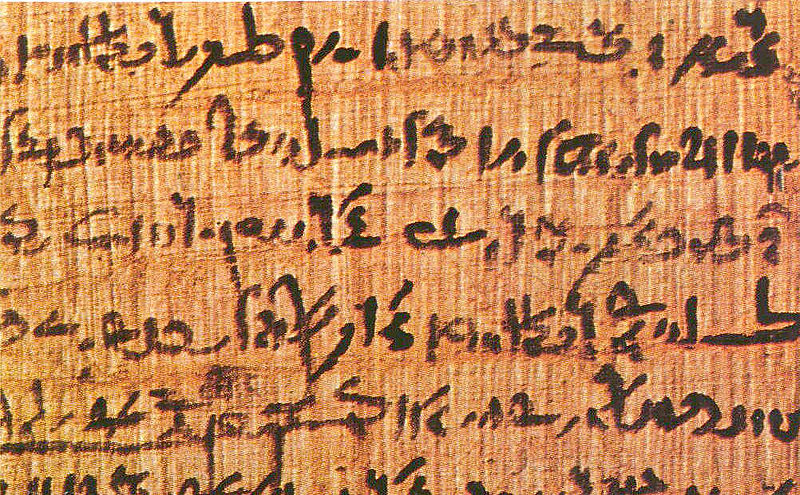

What is papyrus?

Papyrus is probably the best-known paper-like writing surface. Original version of papyrus is made from a plant of the same name. Our term, paper, comes from the Greek word, papyrus. Papyrus, which comes from Egypt, was also used in both Greece and Rome. For almost 4000 years it was the primary writing surface for the Greek-Roman world.

The Papyrus plant has a tall, thick multi-layered stalk. To make a writing surface, these layers are split, flattened, and placed side by side. Additional layers are placed perpendicular to and on top of the first layer. The stalks are then pressed, dried, and dressed with paste, before it is beaten flat and smooth. The papyrus is then ready as a writing surface.

Papyrus was used for literary documents, administrative documents , receipts, and various other private and official documents.

True Paper

"To be classed as true paper, the thin sheets must be made from fiber that has been macerated until each individual filament is a separate unit; the fibers are then intermixed with water, and, by the use of a sievelike screen, are lifted from the water in the form of a thin stratum, the water draining through the small openings of the screen leaving a sheet of matted fiber upon the screen's surface. This thin layer of intertwined fiber is paper."

Parchment:

Is a thin material made from hide; often calfskin, sheepskin, or goatskin, and often split. Its most common use was as a material for writing on, for documents, notes, or the pages of Book, Codex or Manuscript. It is distinct from Leather in that parchment is limed but not tanned; Therefore, it is very reactive to changes in relative humidity and is not waterproof. Finer-quality parchment is called vellum.

Vellum: Is derived from the Latin word “vitulinum” meaning "made from calf", leading to Old French “Vélin” ("calfskin"). It is mammal skin prepared for writing or printing on, to produce single pages, scrolls, codices or books. It is a near-synonym of the word parchment, but "vellum" tends to be the term used for finer-quality parchment.

Vellum is generally smooth and durable, although there are great variations depending on preparation, the quality of the skin and the type of animal used. The manufacture involves the cleaning, bleaching, stretching on a frame (a “herse”), and scraping of the skin with a hemispherical knife (a “lunarium” or “lunellum”). To create tension, scraping is alternated with wetting and drying. A final finish may be achieved by abrading the surface with pumice, and treating with a preparation of lime or chalk to make it accept writing or printing ink. Modern "paper vellum" (vegetable vellum) is used for a variety of purposes, especially for plans, technical drawings, and blueprints.

A codex (Latin caudex for "trunk of a tree" or block of wood, book; plural codices) is a book made up of a number of sheets of paper, vellum, or similar, with hand-written content, usually stacked and bound by fixing one edge and with covers thicker than the sheets, but sometimes continuous and folded concertina-style. The alternative to paged codex format for a long document is the continuous scroll. Examples of folded codices are the Maya codecs. Sometimes the term is used for a book-style format, including modern printed books but excluding folded books.

Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablet, its gradual replacement of the scroll, the dominant form of book in the ancient world, has been termed the most important advance in the history of the book prior to the invention of printing. The spread of the codex is often associated with the rise of Christianity, which adopted the format for the Bible early on. First described by the 1st-century AD Roman poet Martial, who praised its convenient use, the codex achieved numerical parity with the scroll around AD 300, and had completely replaced it throughout the now Christianized Greece-roman world by the 6th century.

The codex holds considerable practical advantages over other book formats, such as compactness, sturdiness, ease of reference (a codex is random access, as opposed to a scroll, which is sequential access, and especially economy of materials; unlike the scroll, both recto and verso could be used for writing. Although the change from rolls to codices roughly coincides with the transition from papyrus to parchment as favorite writing material, the two developments are quite unconnected. In fact, any combination of codices and scrolls on the one hand with papyrus and parchment on the other is technically feasible and well attested from the historical record.

Although technically even modern paperbacks are codices , the term is now used only for manuscript (hand-written) books which were produced from Late antiquity until the Middle Ages. The scholarly study of these manuscripts from the point of view of the bookbinding craft is called codicology; the study of ancient documents in general is called paleography.

Manuscript culture uses manuscripts to store and disseminate information; in the West, it generally preceded the age of printing . In early manuscript culture monks copied manuscripts by hand, mostly religious texts. Medieval manuscript culture deals with the transition of the manuscript from the monasteries to the market in the cities, and the rise of universities. Manuscript culture in the cities created jobs built around making and trade of manuscripts, and typically was regulated by universities. Late manuscript culture was characterized by a desire for uniformity, well-ordered and convenient access to the text contained in the manuscript, and ease of reading aloud. This culture grew out of the Fourth Lateran Council and the rise of the Devotio Moderna, and included a change in materials (switching from vellum to paper), and was subject to remediation by the printed book, while also influencing it.

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders (marginalia) and miniature illustrations. In the most strict definition of the term, an illuminated manuscript only refers to manuscripts decorated with gold or silver, but in both common usage and modern scholarship, the term is now used to refer to any decorated or illustrated manuscript from the Western traditions. Comparable Far Eastern works are always described as painted, as are Mesoamerican works. Islamic manuscripts are usually referred to as illuminated but can also be classified as painted.

And Now A Bit on...

The History of Writing

The history of writing records the development of expressing language by letters or other marks. In the history of how systems of representation of language through graphic means have evolved in different human civilizations, more complete writing systems were preceded by proto-writing, systems of ideographic and/or early mnemonic symbol. True writing, in which the entire content of a linguistic utterance is encoded so that another reader can reconstruct, with a fair degree of accuracy, the exact utterance written down, is a later development, and is distinguished from proto-writing in that the latter typically avoids encoding grammatical words and affixes, making it difficult or impossible to confidently reconstruct the exact meaning intended by the writer unless a great deal of context is already known in advance. One of the earliest forms of written expression is cuneiform.

The Invention of the Printing Press Was Truly the First Means of Mass Communication.

Below you will find some information on this huge game changer in the way the world communicates today.

This is covered, in our timeline as well.

Watching the Following Video will help guide you into how the printing press works, and what it has done for society today.

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468) was a man of many talents. He was a true innovator of his time. Gutenberg was named one of TIME Magazine’s “Top Ten Greatest People” right next to Einstein, Michelangelo and Martin Luther King Jr.(www.TIME.com). Johannes Gutenberg is the father to all mass communication as we see it today. Gutenberg is hailed for inventing the first mechanical printing press around 1439. He is also the inventor of oil-based ink.

Gutenberg “…produced the first so-called modern books, including two hundred copies of a Latin Bible, twenty-one copies still exist. The ‘Gutenberg Bible’ (as it’s now known) required six presses, many printers, and several months to produce” (Campbell, Martin and Fabos 292). This process required financial backing from financier Johann Fust. Fust grew impatient with Gutenberg and their partnership and eventually won a sizable lawsuit against Gutenberg, forcing him to give up all of his printing equipment to Fust (www.answers.com). After the lawsuit Gutenberg had to start all over again. Dealing with one unfortunate situation after another, Gutenberg was reduced to poverty in 1465, and became blind in the last years of his life (www.answers.com). Gutenberg died on February 3, 1468 and was buried in the church of Franciscan Convent.

Without Johannes Gutenberg's invention of the mechanical printing press, we simply would not have mass communication as we do today. Not only books filled with knowledge, ideas and opinions that were able to reach the masses, but the invention of the newspaper, magazines, radio, television, and even the internet would not have been possible without the invention of the mechanical printing press changing the world. Johannes Gutenberg is truly the innovator of mass communication, without him who knows what the world would be like today.

These are all the types of printing through history

William H. Mcguffey

McGuffey Readers were a series of graded primers that were widely used as textbooks in American schools from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century, and are still used today in some private schools and in homeschooling. It is estimated that at least 120 million copies of McGuffey's Readers were sold between 1836 and 1960, placing its sales in a category with the bible and Webster's Dictionary. Since 1961 they have continued to sell at a rate of some 30,000 copies a year. No other textbook bearing a single person's name has come close to that mark.

William Holmes McGuffy, was born September 23, 1800, near Claysville, Pennsylvania. Died 1873.

McGuffy's parents moved from Scotland before he was born and with them they brought the strong opinions on religion and education. Growing up William had a photographic memory and could site the entire book of the bible. thru education and preaching the Gospel he became a teacher at the age of 14, with full class rooms he worked 11 hours a day 6 days a week.

William McGuffy received a classical education at the Old Stone Academy in Darlington, Pennsylvania then went on to Washington college and graduated in 1826. He was offered a position as a professor of languages at Miami University in Oxford Ohio.He became an repeatable lecturer on moral and biblical subjects.

In 1835, the publishing company Truman and Smith had asked McGuffy to create a series of four graded readers for primary-level students. he completed them with in a year and received $1,000 ($21,164 in 2011dallars). Most schools of the 19th century used only the first two in the series of four. The first taught reading by the way of phonics method. Second reader helped the reader understand the meaning of the sentences and providing vivid stories which children could remember. third taught definitions of words and was written at a level equivalent of modern fifth and sixth grader. The fourth was written for the highest levels of ability grammar school level. The content of the readers changed drastically between McGuffey's 1836-1837 edition and the 1879 edition. The revised Readers were compiled to meet the needs of national unity and the dream of an American melting pot for the world's oppressed masses. McGuffey's Readers never entirely disappeared, however. Reprinted versions of his Readers are still in print, and may be purchased in bookstores across the country, including the Museum Shops at the Old Courthouse and Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri. Today, McGuffey's Readers are popular among homes schooled students and in some Protestant religious schools. and they are still highly used and referred back to today.

Books Group

Resources:

What Is Papyrus?" Papyrus History. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2012. http://www.arts-in-company.com/paper/papyrus/history.htm.

Campbell, Richard, Christopher R. Martin, and Bettina Fabos. Media & Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2002. Print.

"Johannes Gutenberg." Biographies. Answers Corporation, 2006. Answers.com 08 Sept.. 2010. Web.

"Johannes Gutenberg." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 09 June 2012. Web. 08 Sept. 2012.

"Top Ten Greatest People." Time Magazine 15 Oct. 1992: n. page. Web.

John Hardin Best. "McGuffey, William Holmes"; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

John H. Westerhoff III. McGuffey and His Readers: Piety, Morality, and Education in Nineteenth-Century America (1978).

John Hardin Best. "McGuffey, William Holmes"; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

John H. Westerhoff III. McGuffey and His Readers: Piety, Morality, and Education in Nineteenth-Century America (1978).

Books Group

Comments (1)

John Anderl said

at 3:30 pm on Sep 28, 2012

Looks good. Pic's are HUGE tho.

You don't have permission to comment on this page.